(Note: the “Thinking out Loud” preview from Spotify starts in the chorus; you should probably bite the bullet and go listen to the whole song to hear the verse sections in question.)

Some History

Let’s Do Forensic Musicology!

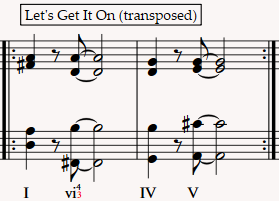

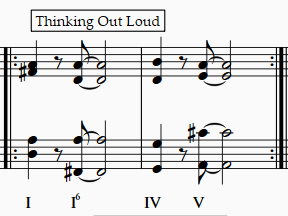

Both songs are based on a sequence of four chords in an ascending pattern, but on “Thinking Out Loud,” the second chord in the progression is slightly different from the one used in “Let’s Get It On.” (Mr. Stewart, the plaintiffs’ music expert, acknowledged the difference in an analysis submitted to the court, but called the two chords “virtually interchangeable.”)

The Songs Are The Same

If this is the case I wanted to make, I’d focus on the bassline and the harmonic rhythm – meaning, the combination of the chords and the rhythm with which the songs progress from one to the next.

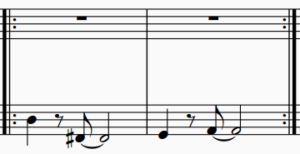

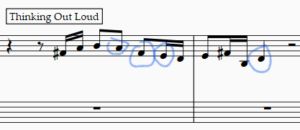

In both songs, this is the bassline (when they’re performed in the same key, D Major):

This is what it sounds like:

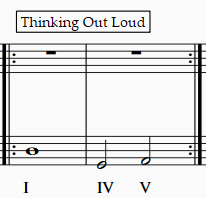

You can probably already see what I mean about the chords moving with the same rhythm. Even though the chords are not exactly the same, the harmonic rhythm definitely is. Here is (roughly) what the chord progressions look and sound like. (It’s been a minute since I’ve done harmonic dictation, so let’s call those inner voices “for demonstration purposes only.”)

Let’s be honest: even though the chord progressions are technically different, they sound pretty much the same, right? More on that later.

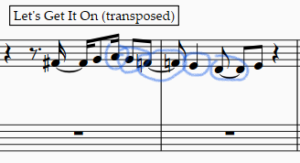

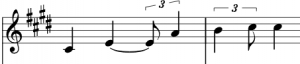

I think you could even argue that even the melodies – though different – use very similar gestures. If we were to look at this in a Schenkerian way (with the disclaimer that Heinrich Schenker was a bad person and also a bad music theorist), you can see that the opening phrase in both melodies have a little sweep up from the 3rd scale degree to the 5th (and past it, in the Sheeran example, but what’s one more ornamental note?), and then they come back down to 1 – skipping scale degree 4 in the Sheeran example, and through a borrowed note in the Gaye/Townsend example, plus some other fun embellishments Gaye adds that I didn’t include here. (The Gaye/Townsend example goes back up to scale degree 2, but that’s over the V chord, i.e., after the point we care about for this argument.)

In addition to the gesture itself, you can see they both start at about the same syncopated point in the measure. Personally, I wouldn’t want to argue this one in court, but someone certainly could try!

The Songs Are Different

Other than the melodic gesture being similar for that one phrase, the melodies are pretty different. Same goes for the lyrics. And the structure – the Sheeran song has a chorus with a different set of chords, whereas the Gaye/Townsend song just kind of hangs out on the same chords.

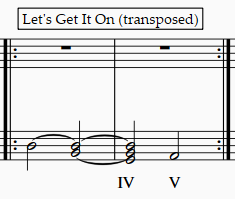

Speaking of chords, let’s take another look at the chord progression that seemed to be the biggest discussion point in court:

The difference, as Sheeran demonstrated in court, is between the vi7 chord (think B minor 7 in the key of D major; it’s in second inversion, so that’s why it says “4/3” in my examples instead of “7” – it’s a voicing thing) vs. a I chord (think D Major chord in the key of D Major). Are those all that different? Well, kinda. Alexander Stewart, the musicologist hired by Townsend’s estate, seems to have argued they’re functionally the same, meaning they both serve to prolong the chord before it. Sheeran, on the other hand, demonstrated (with great theatric flourish) that the chords are qualitatively different – a minor chord sounds different from a major chord. IMO they are both kind of right, but I think Sheeran’s argument is stronger: if you’re going to say the chords are the same, they should be the same. Even though we’re essentially talking about one note that’s present in Gaye/Townsend’s composition but absent in Sheeran’s – as it turns out, that one note can make all the difference.

It’s easier to hear the difference when the chords are arpeggiated. Here is Gaye/Townsend’s vi7 chord:

And here is Sheeran’s I chord:

If I really wanted to get into the weeds, I’d try arguing that the Gaye/Townsend chords can be reduced down to this background progression, where the roots of the I and vi7 chords can be retroactively interpreted as belonging to the IV chord:

Whereas the Sheeran chords can be reduced to this:

But does anyone actually hear the Gaye/Townsend chords that way? Probably not. That’s another argument I wouldn’t want to make in court.

Same Song? Different Song?

I’m actually going to go with option C on this one, which is probably what the jury said when they ruled in Sheeran’s favor: the similarities of the song are coincidental, not intentional. And the reason for the coincidence is the ubiquity of the I-IV-V progression – it’s literally everywhere in Western music. It’s the second progression I used to teach in my classes, right after the more basic version, the I-V progression. Even when you factor in the harmonic rhythm, “Let’s Get It On” is hardly unique. Wikipedia has a whole page on songs that use the I-vi-V-I progression.

Better luck next time, Marvin Gaye and related artists! Ed Sheeran, I guess you don’t have to quit music yet.